2016 has been a horrific year for me personally and, of course, politically--but I’d like to take a moment to reflect on the brighter parts of the year. I:

- said goodbye to one library and hello to another

- survived my first MLIS course through Wayne State University

- organized a snail mail exchange and got a pen pal

- was both delighted and mortified by the revival of Gilmore Girls

- ended a ridiculously toxic relationship

- started managing my first collection

- started a Preschool STEAM program at my new library

- learned how to be happy alone

- continued to fall in love with my cat more and more everyday

- picked apples and made my very first homemade apple pie with my best friend

- took risks, got out of my comfort zone, and made a commitment to grow and learn continually

- practiced self-care like never before

- found a beautiful community of internet friends

- fell in love with Hamilton (and Daveed Diggs!)

- spent even more time with my lovely little sisters

- bought health insurance (that will hopefully not be taken away from me in 2017)

- learned to love the little things and small accomplishments that happen day to day

- reminded myself it's okay to not be okay

I’d like to leave you with one of my favorite accomplishments of 2016. In September, I started my first Master of Library and Information Science course, and I had the opportunity to write about my specific interests and passions regarding library work. I have always believed that library work and social justice are inextricably linked, but what a joy it was to actually sit down and get lost in research on just a few of the incredible, radical children’s librarians, and the myriad ways in which they advocated for our young people. This paper explains why I’m so passionate about what I do, and why I always strive to do more, and to do better.

Children’s Services Led the Way: Social Justice and Library Services to Children

Youth services librarians are widely known as curators of information, storytellers, customer service providers, kindred spirits, teachers, and bibliophiles, but most importantly they are advocates for one of our society’s most vulnerable populations. For children, who are perpetually governed by adults, the children’s department of the public library is a safe haven, a liberatory, radical place, where their needs and interests are prioritized, and their fulfillment is essential. I will argue that from their inception, librarians that serve youth champion diversity, cultural responsiveness, and equity of access. My aim is to examine the ways in which my values and beliefs regarding youth services librarianship, including a commitment to multiculturalism and cultivating a safe space for all children, align with youth services librarians in the field, past and present.

The First Children’s Librarians

Promoting diversity and multiculturalism in children’s literature is a trend that has gained an incredible amount of popularity over the past few years or so—especially with the creation of campaigns such as We Need Diverse Books and blogs such as Disability in Kidlit—although this growing trend is nowhere near a new phenomenon. In “Milestones for Diversity in Children’s Literature and Library Services,” a timeline of diversity milestones in the field written for Children and Libraries, Kathleen T. Horning argues that “as a group, children’s librarians have been on the forefront for diversity from the beginning, striving to serve all children.”

Although the first tax-supported library was established in 1854, it wasn’t until the 1880s and 1890s that libraries began serving children under twelve years of age. In “Libraries and Information Organizations: Two Centuries of Experience,” Christine Pawley spotlights Caroline Hewins and Anne Carroll Moore, who “led a new field in which librarians managed specially designed children’s rooms and services such as storytelling and became cultural authorities in the rapidly growing area of children’s publishing.” Establishing a separate field and space for children was a radical act of advocacy. In “The Librarian Who Changed Children’s Literature Forever,” Laura Miller brings attention to Moore’s revolutionary contributions to the space reserved for children at libraries:

Until the late 19th century, libraries weren’t even considered a fitting place for children under 10, and the first children’s rooms, installed in the 1890s, were initially meant to cordon off noisy young patrons so they didn’t bother the adults. Moore pioneered the children’s room as we still know it today: a homey space with plenty of comfortable, child-size chairs, art on the walls, space for events like storytelling, which Moore almost singlehandedly made a regular feature at libraries. All children’s librarians adopted her credo of the Four Respects: respect for children, respect for children’s books, respect for one’s colleagues, and respect for the children’s librarianship as a profession. None of these was a given before Moore and her cohort came along.

|

| Photo Credit: Miss Moore Thought Otherwise |

Moore saw the humanity in children, rather than seeing them as merely a nuisance, and she found a way to honor that humanity by serving a marginalized population within her library. This act in itself is nothing short of radical, but additionally, she demanded respect for the literature provided for children, and the librarians who serve them: children’s librarianship in its simplest form was born out of advocacy. In Miss Moore Thought Otherwise: How Anne Carroll Moore Created Libraries for Children, a children’s book about her life and accomplishments, Jan Pinborough describes the influence Moore had not just on the creation of youth services departments, but also the culture of the departments:

Miss Moore pushed for other changes, too. She urged the librarians to take down the SILENCE signs and spend time talking with children and telling them stories. She pulled dull books off the shelves and replaced them with exciting ones such as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Swiss Family Robinson. She wrote book reviews and made book lists to help parents, librarians, and teachers find good books for children—and to encourage book publishers to publish better children’s books.

|

| Photo credit: Miss Moore Thought Otherwise |

Charlemae Hill-Rollins and Other Trailblazers of the Field

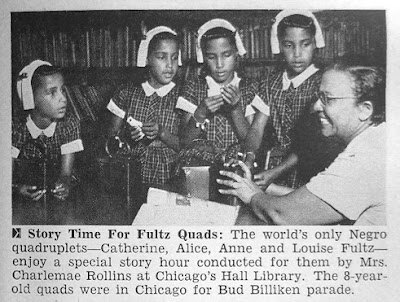

Moore, however, was a white woman, a critic, and held quite a reputable position within New York literary circles throughout her life. Moore may have championed a diverse department, but the heart behind Charlemae Hill Rollins’s advocacy was purely intersectional: she advocated for children, but she also made it her life’s work to push back on stereotypical representations of children of color, and cultivated tolerance and empathy with everything she touched. In a spotlight on her legacy called “Leading Ladies of LIS: Charlemae Rollins,” Catoni describes her activism and cultural responsiveness to her community:

Rollins’ role as an advocate made her a leader in the field. Libraries are community centers, and she worked to change the library in order to suit the community’s needs. She persuaded her fellow librarians in the Chicago Public Library system to remove books that stereotyped African Americans and wrote to publishing companies to request more realistic representations of African Americans in children’s books. Her bibliography of African American children’s books reached a large audience, which shows how strong her leadership was.

|

| Photo credit: Flickr |

Rollins may have not been the absolute first librarian participating in this kind of activism, but she was the first African American librarian to serve as head of children’s services at the Chicago Public Library, and in 1957, she became the first African American to be elected as president of the American Library Association’s Children’s Services Division. In 1941, Rollins published We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature for Elementary and High School Use through the National Council of Teachers of English, a compilation of recommended books that represent African Americans in a humanizing, well-rounded way. “Representation matters” is a phrase that has recently gained a significant amount of attention, and Rollins was one of the first trailblazers to take this stance publicly and to push back on the dominant culture. “Mirrors and windows” is another phrase that has gained a great deal of traction within the realm of children’s literature, and Rollins was no stranger to this idea either. She believed that representation mattered not only to the African American children who were being represented in a text, but the ways in which children were portrayed mattered for white children and those of different cultures, because those texts provided a window to see into an unfamiliar world:

Children as they are growing up need special interpretations of the lives of other peoples and must be helped to an understanding and tolerance. They cannot develop these qualities through contacts with others, if those closest to them are prejudiced and unsympathetic with other races and groups. Tolerance and understanding can be gained through reading the right books.

|

| Photo credit: Mapping the Stacks |

These texts were more than just literature, but social tools in creating a more empathetic society.

|

| Photo credit: NPR |

Pura Belpré, another trailblazer in the children’s literature world, “started her career by offering library services to children at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, making her the first Latina librarian to work in the New York Public Library.” She championed bilingual storytelling and provided library services to Spanish-speaking children and in 1996, the Pura Belpré award was created through a collaboration between the Association of Library Service to Children (ALSC) and the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking (REFORMA) “to encourage books by Latino/a authors and illustrators about Latino experiences in the United States.”

|

| Photo credit: NPR |

Charlemae Hill Rollins and Pura Belpré are just two advocates out of a myriad of children’s librarians who have worked toward creating more inclusive and safe library spaces in collections and through programming, and while I believe I would never be able to live up to their immense degree of accomplishments, I would like to follow in their footsteps with my library practice to the best of my abilities, and look to them and those like them as mentors and role models.

Public Librarians as Defenders of Human Rights

As an aspiring librarian, and one that is drawn to the field because of my equal love for literature and social justice work, I have always thought of the public library as a community space where all can gather—one that acknowledges and celebrates the unique nuances that make up our individual personhood. More than that, the public library is charged with the duty of serving its specific community’s needs, and plays a huge role in providing equity of access to its most vulnerable patrons. I was unaware, however, that certain communities of librarians have developed a philosophy of librarianship that is derived from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In “Public Libraries and Human Rights”, Kathleen de la Pena McCook and Katharine J. Phenix describe the intersection of library services and human rights advocacy:

Public libraries provide the resources for the still voice within each person to be nurtured and to grow. Public libraries provide a public space for discussion of issues important to the common good. These opportunities occur because public librarians in the United States have developed philosophies of collection development, outreach, and community building that are expansive and inclusive.

Through my research, my ideas about social justice work and public libraries (especially services to children) have been supported and bolstered, and I have discovered that my quest to fuse librarianship and advocacy is not a new one.

|

| Photo credit: Lost and Found Books |

In “No Ordinary Place,” Clare Coffey writes of the solace and refuge she received from her local public library as a child:

But what libraries meant to my childhood cannot be divorced from the physical place…The silence, the anonymity, the apparent vastness of the place, the long rows of shelves and side rooms stocked with forgotten books and hung with oil paintings of forgotten patrons, made the library a more than ordinary place. Owned by no one in particular, it seemed imbued with a wealth of possibility that teemed beneath and on the edges of everyday life. In the library, among books I learned to love and curate, the terms of my encounter with the world slowly shifted. Anyone could be a someone here—and that included me.

Coffey describes the ways in which she could be considered “a someone” within the walls of the library, and it was those advocates for the creation of children’s spaces, for inclusive and accurate collections, and for programming that serves diverse populations of children regardless of their race or native tongue—that made the children’s department of public libraries the sanctuary and safe haven that it is today. Youth services librarians have always, and if I have any say, always will be advocates and activists standing up for the rights of all children, upholding the safe spaces that comfort, teach, and entertain their community’s young people. Anne Carroll Moore, Charlemae Rollins, Pura Belpré, and countless others have set the highest examples and standards, and it will be my absolute honor to follow those examples, to defend those standards, and to champion a new generation of “someones.”

|

| Photo credit: Pinterest |

References

Brown Bookshelf. (2007). A brown bookshelf trailblazer. The Brown Bookshelf. Retrieved from https://thebrownbookshelf.com/2007/11/17/a-brown-bookshelf-trailblazer/

Catoni, L. M. (2015, March 18). Leading ladies of LIS: Charlemae Rollins. The Diverse Library Universe. Retrieved from https://blogs.wayne.edu/diversity21/2015/03/18/leading-ladies-of-lis-charlemae-rollins/

Coffey, Clare. (2016). No ordinary place, The Hedgehog Review, 18(2). Retrieved from http://www.iasc-culture.org/THR/THR_article_2016_Summer_Coffey.php

Felicié, A. M. (2014). The stories I read to children: the life and writing of Pura Belpré, the legendary storyteller, children’s author, and New York public librarian, Centro Journal, 26(1), 193-195.

Horning, K. T. (2015). Milestones for diversity in children’s literature and library services. Children and Libraries, 13(3), 7-11.

McCook, K. P., Phenix, K. J. (2006). Public Libraries and Human Rights, Public Library Quarterly, 25(1-2), 57-73. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J118v25n01_05

Miller, L. (2016, August 5). The librarian who changed children’s literature forever. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/blogs/nightlight/2016/08/05/anne_carroll_moore_the_new_york_librarian_who_changed_children_s_lit_forever.html

Pawley, C. (2015). Libraries and information organizations: two centuries of experience. In S. Hirsch Editor, Information services today: An introduction (10-19). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Pinborough, J. (2013). Miss Moore thought otherwise: how Anne Carroll Moore created libraries for children. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

We Need Diverse Books. (2016). Looking back: Charlemae Hill Rollins. We Need Diverse Books. Retrieved from http://weneeddiversebooks.org/looking-back-charlemae-hill-rollins/